Tim O'Brien

American

Published 1990

Politics | Social/Cultural

| Art | Life

| Pictures | Links

| Glossary | Questions

| Group

Questions | Secondary

Sources

Day

1 | Day 2 | Day 3

Transcript

to

Two Days in October

When

reading a longer work such as a novel, it's best to keep track of the

page numbers of your annotations on a note card for ready reference.

I suggest keeping track of your annotations based on the questions on the Essay #2 Assignment page and on the topics below:

Truth v. fiction;

Courage;

Love;

Loss;

Politics;

Day dreams/hallucinations;

Repetition; Memory; Grief; Coping |

Audio and video we used in

class:

Readings

Introduction

Here we begin a look at a different genre -- the novel. And The

Things

They Carried is a great introduction to this genre

because it will seem very familiar after short stories. It's

constructed from interconnected stories that cumulatively pack

the

emotional punch and sustenance of a novel. We'll be looking at

the

title rather closely: one of the "things" we'll be working is to

figure

out just what this novel is "about" -- and it isn't just "about"

the

war.

The

Times

Political

Given the contentious nature of American involvement in the war,

it's

especially important to understand the political background

surrounding

the war chapters.

In the 50s, the lines between good and evil were clear:

America=democracy=good -- Russia/China= communism=evil. The

Cold War was at the sub-zero mark, with kids practicing the desk

protection system (ducking under their desks for protection when

they

saw the flash of an explosion), people building bomb shelters in

their

back yards, and by the early 60s, enemy nukes on our shores

(Cuba). This led to an undercurrent of malaise disturbing

the

seemingly placid facade of the 50s: fear is a powerful drug,

often

rendering things like reason and morality powerless -- and for

all the

country-clubs and drive-ins and days at the beach with Biff and

Barb,

we were very fearful in the fifties.

When Vietnam seemed headed towards communism in the 50s,

American political and military leaders grew worried that all of

Southeast Asia would gradually succumb to the lure of communism

(the

Domino Theory). This would mean that the subcontinent of

Asia

would be, in the "us v. them" vernacular of the time,

"lost." While the Geneva Accord (1956) stipulated that free

elections were to be held throughout Vietnam to determine its

fate, the

leader of South Vietnam, Diem, blocked the elections, with the

support

of the US (both Diem and the US knew that in free elections, the

Vietnamese people would vote for unification under a communist

rule). The North Vietnamese, tired of waiting for a

political

solution to the country's division, opted for a military one.

Two years earlier, in 1954 (after the French lost their

war [called the Indochina War] in a decisive defeat in Dien Bien

Phu),

the CIA had begun funding covert operations against North

Vietnam (see

Gulf of Tonkin above for how we became more directly

involved). Since the US had just defended (and tentatively

won) a war to defend an Asian country from the evil of communism

(South

Korea), we were primed to act again to support "national

security

interests." Of course, one nation's "national security" is

another's "war of independence," and we found out rather quickly

that

not everyone in Vietnam was ready to welcome the smiling face of

American democracy with open arms. Our response to this

equivocation by Vietnam was simple: as one US military official

said

regarding a Vietnamese hamlet that had been reduced to charred,

smoking

ruins by a napalm strike: "we had to destroy the village in

order to

save it."

The narrator's induction and service in the army occur

in 1968, a year which marks a turning point in American

politics. Four major events occurred that year: the Tet

Offensive; the assassination of Martin Luther King; the

assassination

of Robert Kennedy; and the Democratic Convention in

Chicago. The Tet Offensive, attacks by the North Vietnamese

throughout South Vietnam (including the American Embassy in

Saigon)

during the Vietnamese New Year (Tet) celebrations, weakened

support for

the war among citizens at home. Our officials had been framing

the war

as a "wrap up" operation with the enemy on the run. When

film

of the attacks, including summary executions (see below) and US

soldiers cowering behind walls within the embassy in Saigon, was

beamed

into living rooms in full color, many Americans finally began to

see

that there was a disjunct between what the military said about

the war,

and what was actually occurring on the ground. And this

interpretation is not just idle peacenik speculation: as

the

publication of the Pentagon Papers revealed in 1971 and as then

Secretary of War Robert McNamara has more recently revealed in a

self-serving mea culpa

memoir (In Retrospect, 1996), much of what the

government reported to the American people about the war were,

to be

blunt, lies.

South Vietnamese National Police Chief Brig Gen. Nguyen

Ngoc Loan executes a Viet Cong prisoner in Saigon at the height

of Tet

(1968). This photo and the film of the execution considerably

weakened

American support for the war.

(AP Photo/Eddie Adams)

Click to enlarge

The assassination of Martin Luther King touched off

rioting in most major US cities, and (sadly -- why is it that

someone

has to be martyred to move people?) probably ensured the success

(such

as it was/is) of the civil rights movement. The rioting led

to

an increased police/military presence -- a student of mine

recalled

going to work every morning in Northern Jersey with armored

personnel

carriers rumbling in the streets -- which fed the general

feeling of

unease started by the Tet Offensive.

Still, there was the hope of "doveish" political

leaders, like Bobby Kennedy, who had changed from a "hawkish"

view of

the war in his brother's administration, to a more

reconciliatory

approach towards the conflict. Sirhan Bishara Sirhan ended

this faint ray of hope with a handgun in a Los Angeles hotel.

The photo

on the right shows Kennedy being comforted by a busboy.

The brutal police suppression of demonstrations outside

the Democratic Convention in Chicago -- broadcast to the nation

at

large -- showed a nation at war with itself, and the violence

unwittingly became associated with the Democratic nominee,

Hubert

Humphrey, insuring Nixon's election as president.

The cumulative effect of these events meant that O'Brien

and, of course, the nation faced a society in flux, a time when

accepted political values and beliefs were being challenged; we

had

moved from the paternalism of Eisenhower to the "what you can do

for

your country" of Kennedy, but had yet to agree on what to "do."

The aftermath of the war, which help shape the

narrator's thoughts, included a curtailment of the enlightened

ideals

of President's Johnson's "Great Society" (circa 1964-68) --

freedom

from poverty, illiteracy, etc. -- which were compromised by the

costs

of the war effort. Money that could/should have been used to

counter

social ills was spent financing the war (final cost, 1 trillion

dollars). And of course, the political backlash against

military actions and fear of causalities has changed America's

foreign

and military policy. We're more wary of incursions into

other

territories for fear of body bags (notice how quickly we exited

Somalia

after "Black Hawk Down"), and rely now on "Smart Bombs" and

other

ordnance instead of soldiers on the ground. Unfortunately, one

of the

main "lessons" our government has learned from the war is to

control

information and to spread misinformation (no more reporters

tagging

along in helicopters to send compromising footage back home to

the

folks in Peoria).

And

then, of course, there's the rhyming of history: here we are, four

decades (and counting) after the end of the Vietnam war, and we're

still trying to bring democracy to other foreign lands at the point of

a gun.

Social/Cultural

The events in the novel occur against a background of

liberation:

Women's Rights, Civil Rights, youth rights . . . in other words,

a time

of change. The various constituencies agitating for change were

responding to the 50s (cf. Modernist's response to the

repression of

the 19th century), a time of drive-ins, stay-at-home moms, and a

conservative government embodied by Dwight Eisenhower. In

the

50s, if you were different, you were a beatnik and your opinions

were

marginalized. If you protested too strongly, you could find

yourself

labeled a communist (remember, the temperature of the Cold

War was around zero at

this time), and find yourself out of a job (McCarthyism). This

was

a time when God, Guns and Guts ruled the land: the words "under

God" were inserted in the Pledge of Allegiance in the 50s, and

Westerns

(white man with a revolver and courage saves the world) were all

the

rage. But the war years of the novel takes place in the

interim period, when America was making the change from Leave it

to

Beaver to Laugh-In (which was, if you aren't familiar with it, a

politicized Saturday Night Live).

Yet while many agitated for change, there were some --

who Nixon mistakenly labeled "the silent majority" -- who wanted

things

to remain the same. Think of it as Levitt

town v. Haight Asbury -- hard hats v. egg heads (note that the

segregationist George Wallace was a candidate for president in

1968). And that last contrast gets at an essential part of

the

debate of the war -- and of American culture in general:

anti-intellectualism. Consider the loci of the protests:

college campuses. For those in favor of the war, the

problem

with the protesters was that they thought too much. Joseph E.

Sintoni,

a soldier who later died in the war, wrote to his fiancee' "The

press,

the television screen, the magazines are filled with the images

of

young men burning their draft cards to demonstrate their

courage. Their

rejection is of the ancient law that a male fights to protect

his own

people and his own land" (252). He adds "We must do the job God

set

down for us. It's up to every American to fight for the

freedom we hold so dear. We must instruct the young in the

ways of these great United States"(252). Joseph represents the

Levitt

town approach to war -- God, Guns and Guts. The ideals of

the

Haight can be found in Mark Rudd's open letter to his college

president, Grayson Kirk, of Columbia University: "We do have a

vision

of the way things could be: how the tremendous resources of our

economy

could be used to eliminate want, how people in other countries

could be

free from your domination, how a university could produce

knowledge for

progress, not waste, consumption, and destruction . . . . how

men could

be free to keep what they produce, to enjoy peaceful lives, to

create"

(248). These two competing visions were at the root of

American views of the war and its causes -- and the catalyst for

much

of the internal strife.

Of course, I'm painting a rather rigid

dichotomy. Many Americans rejected Sintoni's jingoism just

as

they objected to Rudd's idealism. And there were many who,

I'm

sure, really could care less as long as the Dodgers still played

and

the Milwaukee's' Best still flowed. Sad, isn't it, how some

things never change.

For a "you are there" perspective, read Don Duncan's "The

Whole

Thing Was a Lie!," a serviceman and participant's take

on the Vietnam war. This is an edited version: see me for the

entire

essay.

It's important to note that, contrary to the stereotype

of Vietnam veterans as seething cauldrons of repressed anger

ready to

explode at a moment's notice, most veterans readjusted to

civilian life

as well as veterans of previous wars. Yet serving in Vietnam was

a

different experience from previous war. For one thing,

soldiers were not assigned for the duration of the conflict:

soldiers

only had to serve 365 days of combat duty, and then were rotated

out of

country (as opposed to "in-country"). This abbreviated service

meant

that soldiers did not have the opportunity to form the lasting

attachments to others in their units that would help provide

emotional

support -- and a sense of continuity. Additionally, the

alien

country and culture lead to a disorienting feeling, as did the

nature

of guerrilla warfare (where your enemy could be the smiling

woman

selling you mangoes). And of course, some soldiers faced a

hostile reception upon returning home. These all

contributed

to the post traumatic stress syndrome suffered by some

veterans. This wasn't a new disease -- it's simply a label

for

an affliction that has affected soldiers for centuries upon

their

return to civilian life.

The

Arts

Two broad movements form the aesthetic background to this novel:

the

surrealism of the 60s, and the post-modernism of contemporary

literature. Surrealism adds a hallucinatory quality to a work of

fiction, the prose equivalent of the swirling washes of color

and

stream of consciousness imagery of the psychedelic posters (and

those

mind-bending Grateful Dead and Allman Brother's album covers)

from the

60s and 70s. Yet the surrealism on display in the novel

isn't

merely a period piece; it's our old friend the unconscious, the

Id,

showing up again to topple the existing order. It's a

method

of conveying the often tortured and tortuous mental landscape of

a mind

in conflict with itself.

The Post-modern aspect of the novel appears in its

self-referential quality -- more particularly labeled

metafiction,

which means fiction about the nature of fiction itself. While

this has

a long history (Tom Jones by Henry Fielding is an 18th century

example), the emphasis on form in Modern literature led to an

exposure

of the same (i.e. illustrating the artifice of fiction) in much

of

contemporary literature. Literary movements usually move in

reactionary

cycles: authors grow frustrated with established conventions and

have

to reinvent the art of literature to fit the new age. Thus, in

Things

They Carry, you'll find a writer who ironically discusses the

act of

writing itself: he both tells a great story -- and tells us he's

telling a great story. And watch for references to the

"author" himself -- and be aware that post-modern writers love

to play

around with the idea of the narrator/author.

Shakespeare's "Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer's Day"

is relevant here and will be discussed in class

XVIII (765 in Textbook)

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer's lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm'd,

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature's changing course untrimm'd:

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st,

Nor shall death brag thou wander'st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow'st,

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

The

Life

Tim O'Brien grew up in small-town Minnesota (where he

experienced

first-hand the clash of small-town morals with the outside

world). He credits his mother, a first grade teacher, with

investing in him the importance of paying attention to details

when

writing. Attending a state college in Minnesota, he majored

in

Political Science and was elected the student body

president. Upon graduation, he was drafted in August of

1968,

and served seven months as a radio operator in Chu

Lai. Wounded twice, he spent the last five months of his

Vietnam tour as a clerk, away from combat duty. After his

tour

of duty, he attended graduate school at Harvard, and completed

(but did

not defend) his dissertation, and began writing for the

Washington Post in 1972 (Kaplan 1-9). His first book, If I Die in a Combat

Zone, a memoir of his service in Vietnam, established him as a

writer

of talent, and his novel Going After Cacciato (which is also set

in

Vietnam), after winning the National Book Award in 1979, vaulted

him

into the upper ranks of American authors.

He has a very generous spirit as a writer, regularly

appearing at workshops (my office mate worked with him years ago

and

found him refreshingly unpretentious and "down to earth") and

giving

copious interviews on his craft. On his penchant for writing

about

Vietnam, he noted "[my] concerns as a human being and . . . as

an

artist have at some point intersected in Vietnam -- not just in

the

physical place, but in the spiritual and moral terrain of

Vietnam" (qt.

in Kaplan 4-5). And as this novel makes clear, this is a

terrain well worth exploring.

"I'll

Take You There"

Unless marked otherwise, the images below are

from wikimedia

|

Click to enlarge

My Lai Massacre

* For a compelling overview of My Lai, see the

page below (note -- it's on a rather repellent site, but

the material

on the page I've linked is quite good).

http://www.rotten.com/library/history/war-crimes/my-lai-massacre/

Another good My Lai site

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/My_Lai_massacre

Long and detailed article on the massacre

http://www.crimelibrary.com/notorious_murders/mass/lai/index_1.html

For a contemporary version of My Lai, see the

following

http://www.rotten.com/library/crime/prison/abu-ghraib/

|

click to enlarge

Visual of a soldier's life: lots of "humping."

Walking along a dike separating rice patties

(click to enlarge)

|

|

Effects of napalm. See article

on

this famous picture

|

Baby water buffalo

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_4LJig4kYi8s/TSmtXNyXFCI/

AAAAAAAABJU/6lNV6S5pMsc/s1600/DSC02961.JPG

|

Links

For additional photos, try this link from the New York Times.

Additional pictures can

be found here.

Connections between Vietnam and Iraq? See Ron

Kovic's

essay published on Truthdig. Note: it's a partisan

view.

The New York Times is

running a series of essays on the year 1967 of the Vietnam war. It's a

great source for personal reflections and more interpretative

essays. For backgrounds on the war -- back to pre WWII -- see "The 30 Years War in Vietnam."

Vietnam

Glossary

In this novel you'll find several military acronyms, topical

references, etc., that may need a bit of explaining. Hence,

a

glossary.

Let's clarify three things, right off the bat.

Vietnam: Area/country in

southeast Asia with an independent language, culture, and

government. Partitioned into North and South Vietnam in

1954

in response to the western fear of communism, the two countries

were

rejoined in 1976 after the fall of the South Vietnamese

government. During the war years, the country was bisected

by

the DMZ (Demilitarized Zone).

North Vietnam: The

communist controlled area of Vietnam -- they wanted to unite the

country under one rule. South Vietnam's and, because of the

Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), our enemy.

South Vietnam: The

non-communist, nominally democratic (but really autocratic) area

of

Vietnam. Our ally due to SEATO which stated that any member

which comes under attack will enjoin all members in its

defense. South Vietnam and America were members: North

Vietnam

was not.

|

Interactive Vietnam map

click to view

|

|

Period Maps (circa. 1968) click to view

1968 (period map)

http://www.vietvet.org/visit/maps/1968map.htm

|

AK-47: Standard issue rifle

used by North Vietnamese. Cheap, reliable,

deadly. Now a designer weapon for drug dealers.

America: love it or leave it: phrase

adopted by the great unthinking class as a response to protests

against

the war. It stifles dissent by suggesting that "you're

either

with merica', or you're with the terrorists." Oops, wrong

war

-- but same idea.

ARVN Army of the Republic of

Vietnam. Considered poor fighters by US service men.

Bao Dai: The "playboy

emperor." Last emperor of Vietnam, courted and assisted by

both communist and American regimes because "the people"

accepted him

as a sovereign ruler. An opportunist, and for that reason,

a

survivor.

Bouncing Betty: a type of land mine.

After a soldier, civilian, or water buffalo would step upon it,

a

little rocket/bomb would shoot up that exploded at about waist

height. Usually deployed by the North Vietnamese.

Claymore: rectangular mine set off

by remote control. It would send a shower of lead in a

triangular

killing field. Usually deployed by Americans. See

picture below

Diem, Ngo Dinh: Autocratic

ruler of South Vietnam from 1955-63. Corrupt, a Roman

Catholic

in a Buddhist country, he was propped up by American officials

because

of his hard line stance against communism. Assassinated by

his

own military in a 1963 coup.

domino theory: argument used by

American political leaders to support a war against

communism. They believed that if one country fell to

communism, then others around it would fall as well (like a line

of

dominoes). What they never seemed to address was why

communism

would prove so attractive. I mean, it's not a virus or

anything, it's merely a political system.

Gook: US military slang for a

Vietnamese person.

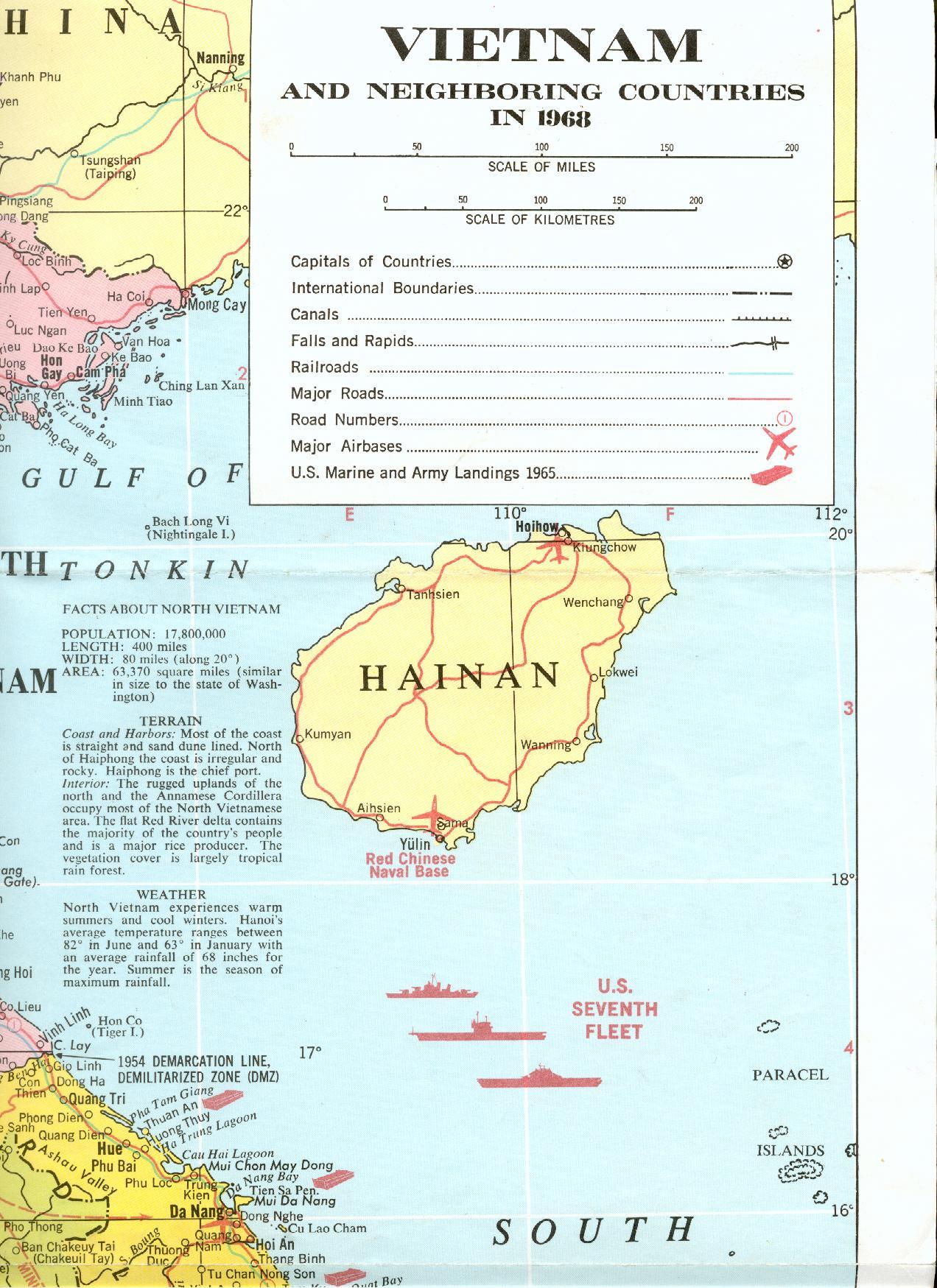

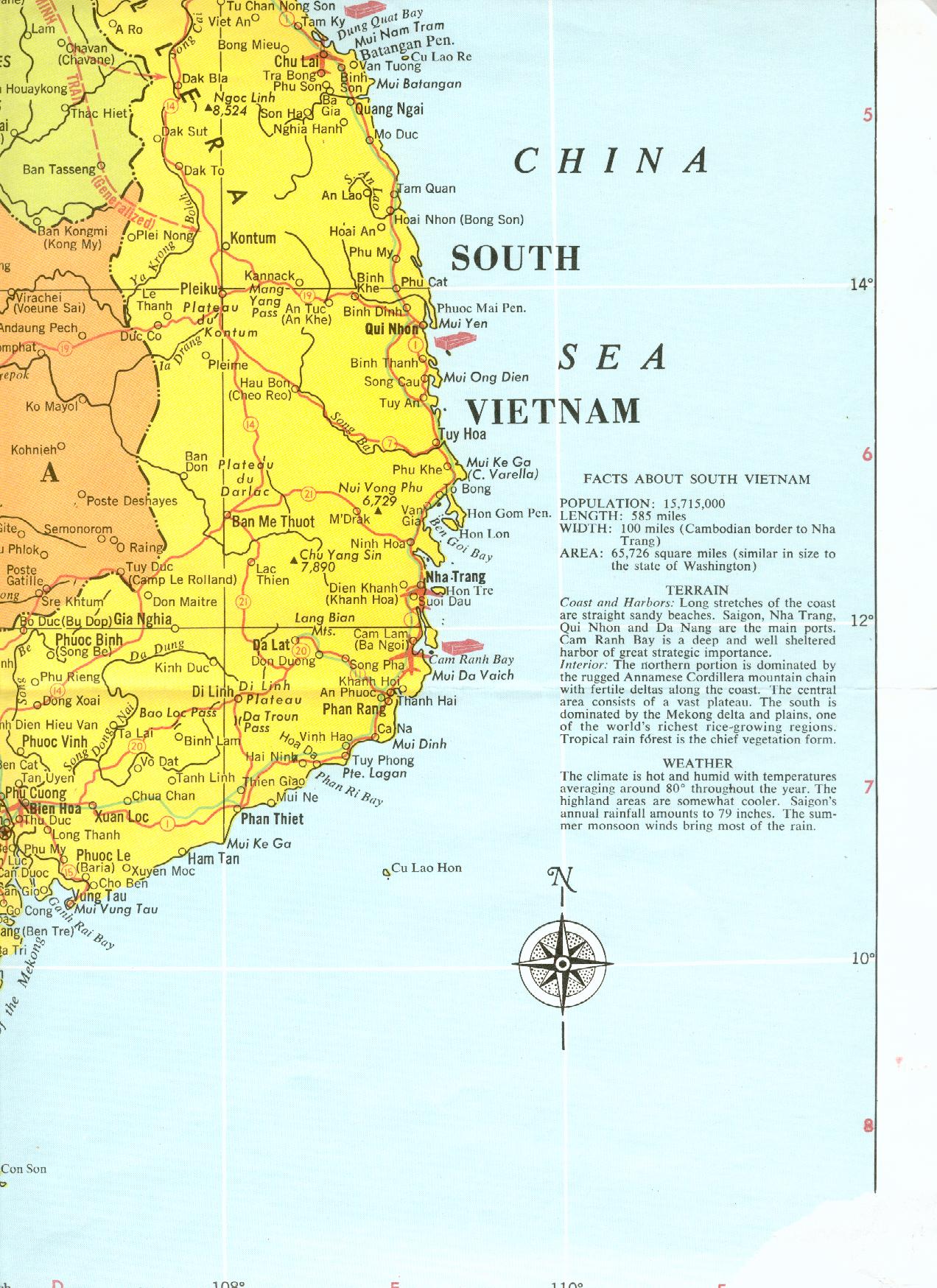

Gulf of Tonkin: located in North

Vietnam (see map above). Important because US military and

intelligence reported that a Navy destroyer, the USS Maddox, was

attacked by North Vietnamese gunboats in 1964, which lead to a

resolution to increase military presence and its role in South

Vietnam. It is now generally accepted that the attack did

not

take place and some feel that the military and intelligence

agencies

perpetuated a hoax to prompt deeper US involvement in the

war.

Hawks and doves: shorthand to

describe support for (hawks) or opposition to (doves) the

war. Prominent hawks from the era include John F. Kennedy

(though he was there before the term really was bandied about),

Barry

Goldwater, Richard Nixon, and Henry Kissinger.

The main dove mentioned in the novel is Senator and Democratic

Presidential Nominee Eugene McCarthy.

Ho Chi Minh: The political and

spiritual (in an agnostic sense) leader of North

Vietnam. In

the 1950s, after reading the Declaration of Independence, he

approached

American officials in France (where he was educated) and asked

them for

his help in overthrowing the French colonial powers. We refused

due to

treaty alliances and because of cheap rubber (Vietnam's primary

export)

and Minh then turned to Russia and China for support.

R&R: Rest and

relaxation. A vacation from the battlefield typically

involving a trip (or trips) to a brothel, drinking, and, if such

was

your preference, drugs. Sleep and good food as well. In

other

words, creature comforts for 19 year old males.

klicks: slang for kilometers

Eugene McCarthy: presidential

candidate in 1968 elections who was against the war. To

support him meant you too were against the war.

M-16: Standard issue rifle used by

the US and South Vietnamese. It was expensive,

semi-reliable,

and deadly. Because of its toy-like look, it has not become

a

designer weapon for drug dealers.

Three for one: 1) M-16 rifle; 2) Flack Jacket;

3) "hootch" or grass house, typical of Vietnamese civilian

villages.

Very flammable -- which helped make napalm (see below) such a

useful

(?) military tool.

from http://s88.photobucket.com/albums/k188

mortar: tube like cannon,

easily hidden, transported, and operated. A favorite of the Viet

Cong.

napalm: bombs filled with jelled

gasoline which ignites on contact with the air. Usually

dropped from jets which resulted in a streak of fire (momentum

of bomb

would spread flame).

tracer rounds: bullets treated with

a chemical to make them flammable on contact. If fired at

night would leave a streak of light -- handy for aiming, though

it also

made a great target.

Sterno: metal cans of jelled

petroleum. Pop the top, instant stove.

Tran Hung Dao: Vietnamese general

who repelled Mongol invasions in the 13C. (roughly

equivalent

to George Washington in America -- i.e. military founding

father).

Tot Dong: field where the Vietnamese

defeated the Chinese in 1426, leading to their independence

(think

Bunker Hill).

VC: short for Viet Cong, the

communist guerrilla fighters who lived in South Vietnam.

Walked point: walking at the head of

line of soldiers in a patrol. Dangerous because you would

be

the first person to encounter a landmine, sniper, or ambush.

Willie Peter: Short for White

Phosphorous, a incendiary explosive material.

Focus

for each day

Day 1

Focus:

Reading

novels in general -- focusing in and looking at the whole;

historical/cultural background;

characters in the story; truth and reality

|

"To

read a novel

is a difficult and complex art [ . . . . ] You

must be capable not

only of great fineness of perception, but of great

boldness of

imagination if you are going to make use of all that

the novelist -- the

great artist -- gives you" (Woolf).

|

|

"One

explanation

for O'Brien's habit of varying and echoing and

repeating

phrases

and thoughts and scenes and stories in his writings is

that this

stylistic

device mirrors his notion of fiction as a means for

conveying the

fluidity of

all experience. According

to O'Brien's

approach to fiction, one can use the same phrase or

tell the same story

again

and again, and yet each time one does so, the phrase

or the story

somehow takes

on a new character. Fiction

and

language

for him do not mirror life: they transform life"

(Kaplan 18).

|

Kaplan,

Steven.

Understanding

Tim O'Brien. Columbia, South Carolina: U of South

Carolina, 1995. Print.

Woolf, Virginia. "How Should One Read a Book?" The

Second Common Reader. 1935. Gutenberg.org.

Web. 3 August 2015.

Using Note Cards

Focusing

in

and looking at the whole

By

this

I mean learning to move between individual stories and chapters,

and then applying them to a larger reading of the novel as a

whole. See

the chapters "Stockings" then "Church" for this kind of

connection.

You'll

need to develop a "reading," "interpretation," or "approach" to

the

novel to understand. Note: there are many different readings,

interpretations, or approaches.

How a summary misses the point:

How to tell a True War Story

Rat

Killey, the medic writes to a friend's sister about the death of

her

brother. The narrator keeps pointing out the ways to tell

that

this is a true story. His friend was playing catch with

Rat,

and

stepped to the side coming down on a mine. He goes into

great

detail about the gore of the accident, then says that the

story

is fake.

Characters: distinguish between

them

Tim

O'Brien: Jimmy Cross: Martha: Elroy Berdhal: Kiowa: Ted

Lavender: Lee

Strunk: Dave Jensen: Rat Kiley: Mary Anne: Mark Fossie: Norman

Bowker:

Kathleen, Azar, Bobby Jorgenson, Linda:

Historical/cultural background

- What

do you

know about the Vietnam War.

- The

60s

were a time of change and turmoil. As a society,

America

moved

from an acceptance of authority (the Eisenhower years

[ex-general]

stasis) to a questioning of authority (JFK [young --

committed to

change]); From

Levitt

towns to communes

- What

does

change do to some people?

- Look

at

epigram of novel -- From what war is it from? Why the

Civil

War; why not, say, WWI or WWII?

- Go

to page

40ish of novel -- then 45.

Timeline

1954 CIA funded covert operations against North Vietnam in 1954

1957 Little Rock Schools integrated w/ federal troops

1961 Freedom rides in the south

1963 Kennedy Assassinated

1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

1967 Seventy cities experience black riots

1968 Tet Offensive

1968 Martin Luther King

1968 Robert Kennedy assasisanated

1975 Last helicopters leave South Vietnam

Truth and reality

- The Two Hilters

- Let's

start

with the writer: How many Tim O'Brien's are there? Are

they

the same?

- (Bring

in

several novels that do not have "A Work of Fiction"

written on

them) What's odd about the title page compared to the other

novels?

- What

about

the dedication then?

General questions

"Things They Carried"

- Consider the

following sentences "It was't cruelty, just stage presence.

They were

actors" (20). Why? Why characterize the soldiers as "actors"?

And what

effect does this have on their actions -- and our

understanding of

them?

- Why the

accumulation of specific weight and specific detail in the

lists of the

things they carry? What effect does it have on the reader? And

how do

they contrast with the other paragraphs in the story?

- What is LTV.

Cross crying about (17)? What is this story really "about"?

- Why is this

the first story/chapter in the novel? How does it connect to

the other

stories?

"Spin"

- How does

this story function as a foreshadowing for the rest of the

novel? Pick

out pages/details and explain.

"On the Rainy River"

- Why does the

narrator work in a pig slaughter house? Does it foreshadow his

experiences in Vietnam in some way? See, especially, page 42.

- Why is Tim

so upset with the people that support the war?

- What is

"courage" to the narrator? Given the story, do you agree or

disagree

with him?

- What is

Elroy Berdhal's function in the story? Why not just have

O'Brien

standing on a windswept prominence, debating whether he should

go to

Canada or not? What does Berdhal represent?

Day 2

Focus:

Assign secondary source readings; use of

symbolic/figurative

language; loss;

memory; revenge;

truth

and reality again -- why the book "lies" to readers

Psychology and fiction

"What

is clear in all these cases --whether of imagined or real

abuse in

childhood, of genuine or experimentally implanted

memories, of misled

witnesses and brainwashed prisoners, of unconscious

plagiarism, and of

the false memories we probably all have based on

misattribution or

source confusion -- is that, in the absence of outside

confirmation,

there is no easy way of distinguishing a genuine memory or

inspiration,

felt as such, from those that have been borrowed or

suggested, between

what the psychoanalyst Donald Spence calls 'historical

truth' and

'narrative truth'" (Sacks).

Sacks, Oliver. "Speak, Memory." The

New York Review of Books.

21 February 2013. Web. 17 February 2013. |

On

details leading people astray:

"The most coherent stories are not necessarily the most

probable, but

they are plausible, and the notions of coherence,

plausibility, and

probability are easily confused by the unwary"

"The uncritical

substitution of plausibility for probability has

pernicious effects on

judgments when scenarios are used as tools of forecasting.

Consider

these two scenarios, which were presented to different

groups, with a

request to evaluate their probability:

- A massive flood somewhere in North America next

year, in which more than 1,000 people drown

- An earthquake in California sometime next year,

causing a flood in which more than 1,000 people drown

The California earthquake scenario is more plausible than the North

America scenario, although its probability is certainly smaller. As

expected, probability judgments were higher for the richer and more

detailed scenario, contrary to logic. This is a trap for forecasters

and their clients: adding detail to scenarios makes them more

persuasive, but less likely to come true. See "Good Form"

(details=squirrel) and end of "How to Tell" (missing the point).

On the difference between memory and experience:

"A

comment I heard from a member of the audience after a

lecture

illustrates the difficulty of distinguishing memories from

experiences.

He told of listening raptly to a long symphony on a disc

that was

scratched near the end, producing a shocking sound, and he

reported

that the bad ending "ruined the whole experience." But the

experience

was not actually ruined, only the memory of it. The

experiencing self

had had an experience that was almost entirely good, and

the bad end

could not undo it, because it had already happened. My

questioner had

assigned the entire episode a failing grade because it had

ended very

badly, but that grade effectively ignored 40 minutes of

musical bliss.

Does the actual experience count for nothing? Confusing

experience with

the memory of it is a compelling cognitive illusion -- and

it is the

substitution that makes us believe a past experience can

be ruined. The

experiencing self does not have a voice. The remembering

self is

sometimes wrong, but it is the one that keeps score and

governs what we

learn from living, and it is the one that makes decisions.

What we

learn from the past is to maximize the qualities of our

future

memories, not necessarily of our future experience. This

is the tyranny

of the remembering self."

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

|

"Rainy River"

- Finish background on war and shift to

language

- Amour meat packing -- gun, etc. He's been

in "war" and doesn't like it.

- Move to Elroy: and courage

"Speaking of Courage"

- What do you make about the lake? How is it connected

to the war?

- What day of the year is it?

- Why does he keep riding around the lake

- Why include the scene at the drive in?

What's going on there?

- How does the very end of the story replicate the war?

- Why does he take a sip of the disgusting water?

"Good Form"

- Why include this story/essay?

- What's the difference between happening truth and

story truth?

- Go to Colin Powell videos

"How to Tell a True War Story"

- Discuss the nueroscience of memory: how it's all

constructed and how the only true memory is the first one.

- Go to the different times Lemon dies

- Love story: the letter Kiley writes: it's clear he

feels love

- but mention how he's stuck in a Vietnam mode and

can't tell that what he writes to the sister is creepy.

- Here

or earlier, analogy of me on trial for murder: three people:

me, friend

who is my alibi, person in holding cell with me the night I

was

arrested -- and who has been promised reduced time if he

testifies.

- my buddy stumbling over what we were doing that

night,

- person I was in holding cell with says

Day

3

Focus:

Getting a handle on your interpretation -- choosing a

reading/approach

to the novel; connecting the ideas in the novel to sources;

questions

for Essay #2

From

Aristotle's Poetics

"The true difference is that one relates what has

happened, the other

what may happen. Poetry, therefore, is a more

philosophical and a

higher thing than history: for poetry tends to express the

universal,

history the particular. By the universal I mean how a

person of a

certain type on occasion speak or act, according to the

law of

probability or necessity; and it is this universality at

which poetry

aims in the names she attaches to the personages."

http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/poetics.1.1.html

Written 350 B.C.E Translated by S. H. Butcher |

Relativism

In philosophy, the position that all value judgements (e.g. ethics,

morality, and truth) are relative to the standpoint of the beholder. To

put it another way, relativism does not accept that there is

an absolute ground or reference point that could provide an objective

guarantee that things are not necessarily the same as they are

perceived to be by a given subject. If one is neither religious nor a

hard-headed realist,

then some version of relativism is unavoidable, which creates

a great many difficulties for philosophers in this situation because it

is easy (though not necessarily accurate or just) to turn this into an

accusation. Postmodernism has

been taken to task on numerous occasions for precisely this reason: it

challenges the plausibility and possibility of an absolute ground. As a

consequence it has been charged with being apolitical, ahistorical,

unethical, and so on, because all these things -- politics, history,

ethics, etc. -- are said to require a ground to function properly. As Jean-Francois Lyotard shows, the problem with relativismis that it enables historical revisionists such

as Holocaust-deniers to claim that their position is as valid as any

other. His solution, only partially successful, is to focus on what he

calls truth-regimes. Alain Badiou offers a slightly different solution to the same problem via a retooling of Jean-Paul Sartre's

concept of the project. Badiou's project is that which attracts

political conviction, i.e. a belief equal in strength to religious

belief. See also anti-foundationalism.

Buchanan, Ian. "relativism." A Dictionary of Critical Theory. Oxford University Press, 2010. Oxford Reference.

2010.

http://www.oxfordreference.com.libproxy.ocean.edu:2048/view/10.1093/acref/9780199532919.001.0001/acref-9780199532919-e-595.

Accessed 21 Dec. 2017.

And for a longer, more textured discussion, see this definition.

|

Quick review of Secondary Sources

"In the Field"

- How does the metaphor of the "shit field" resonate

throughout the story. See, for example, bottom of page

163.

- Who

does O'Brien (author) suggest contributed to Kiowa's

death?

(164,

166, 170, 176, 179) Why does he have different people take the

blame --

what does this ultimately show about the cause of Kiowa's

death?

And who showed Kiowa the picture of Billie?

"How to Tell a True War Story"

- Perception

- Different times Lemon dies

- Lemon's sister v. Rat's letter

- VC Baby Water buffalo:Why more upset

"Lives of the Dead"

- First

sentence: how can a story save your life? How does it

"save"

Linda's life? Does it save anyone else's life? Does lack

of a

story cause anyone to die?

- End of the novel -- metafiction

- What's the function of Linda? Why add her to the

story? What add her at the end instead of at the

beginning?

Quick question: what's the purpose of "Ghost Soldiers"?

Any general comments/questions?

Review Essay Questions and show possible divisions with thesis

statements.

Questions

to Mull Over As You Read

General questions

- Consider the

relevance of the following quote to the entire story:

"Absolute

occurrence is irrelevant. A thing may happen and be a total

lie,

another thing may not happen and be truer than the truth"

(83). How

does this relate to 1) the story/novel itself; 2) the nature

of story

telling in general?

- Which "True"

is he talking about in the title of the story/chapter ("How to

Tell a

True War Story) -- the "happening-truth" or the "story-truth"

("Good

Form" 179)? How can you tell -- or not tell? Does O'Brien feel

this

distinction is important? Why or why not?

- Trace the

transformation of Mary Anne "Sweetheart:" she changes from

____ to

_____. What could she symbolize? Why/how?

- What

"Courage" is referred to in "Speaking of Courage"?

- How does the

metaphor of the "shit field" resonate throughout the story.

Why not,

for example, a regular muddy field?

- How is

imagination something positive in the book? (consider, for

example,

"Lives of the Dead," "Good Form"). How is it negative ("Thing

They

Carried," "Ghost Soldiers" -- other stories?)? What's the

point?

- Why does

Bowker taste the water at the end of "Speaking of Courage"

(173)?

- What can the

narrator O'Brien do that Bowker cannot? How can this ability

save the

narrator? (Consider "Notes")

- How does the

narrator change? From what to what? (Take this in stages --

use

particular chapters to trace this change) What stories show

this? Where

in those stories? Does your opinion of the narrator change?

- What's Linda

doing in the novel? How does she or her story connect with

other

themes? If she and that chapter was not in the novel, how

would it

change? Another way of looking at this is why does "Lives of

the Dead"

conclude the novel?

- In an

interview, O'Brien stated "If there is a theme to the whole

book it has

to do with the fact that stories can save our lives" (qtd. in

Coffey

202). So, where's the theme? Point to at least three quotes

that prove

this.

Group

Questions

Group questions #1

- What is

Elroy Berdhal's function in the story? Why not just have

O'Brien standing on a windswept prominence, debating whether

he should

go to Canada or not? What does Berdhal represent?

- Think about

the following story connections: "Things They Carried" --

"Love" /

"Speaking of Courage" -- "Notes." What is O'Brien

attempting

to construct/show with these stories pairs? It may help

to

connect these story pairs to "Good Form." Why does O'Brien

include this

("Good Form" chapter? Why doesn't he place this chapter

earlier?

- In an

interview, O'Brien writes that "If there is a theme to the

whole book

it has to do with the fact that stories can save our lives"

(qtd. in

Publishers 202). How does the novel show this? Trace out

this

theme in the novel by showing that, indeed, the novel does

argue that

"stories can save our lives."

- Though

ostensibly a war novel, the stories touch on many other issues

as

well. What, for instance, does the novel suggest about

____,

_____, love, courage, how people cope?

Group questions #2

- This novel

is filled with references to

storytelling and writing (this is called metafiction - fiction

about

fiction). Connected to this is the idea that, as O'Brien

mentioned in

an interview, "stories can save our lives." How does this work

in the

novel? Could you divide it into different facets? What

incidents could

you use to prove your point?

- Much of the

novel deals with questions of truth: first, decide on

O'Brien's

definition of truth ("For O'Brien truth is _______." "O'Brien

looks at truth as _____") and

then explain how the novel illustrates this definition. What

incidents show this? How can you divide/classify it?

- What is O'Brien saying about

history? ("For

O'Brien, history is _____" "O'Brien believes that history

_____"). What

ideas/incidents in the novel show this? As above, can you

break down his view of history as ____ into different

categories?

- How do the questions O'Brien

raises in the novel -- the slipperiness of truth, the ease

with which

people can be fooled, the apathy and willful ignorance of much

American

society, etc. -- manifest themselves in 21st century

America? Another way of answering this questions is to

ask

yourself "How is this novel still relevant?"

- How is this

a novel about love? What kinds of love? About coping? About

guilt?

About fear? About _____?

Works

Cited

Kaplan, Steven. Understanding Tim O'Brien.

Columbia, South Carolina: U of South Carolina, 1995.

Rudd, Mark. "We, the Young People." Ordinary

Americans: U.S. History Through the Eyes of

Everyday People. Ed. Linda R.

Monk. Alexandria, VA: Close Up Publishing, 1994.

248-49.

Sintoni, Joseph. "Our Country, Right or Wrong." Ordinary

Americans: U.S. History Through the

Eyes of Everyday People. Ed. Linda

R. Monk. Alexandria, VA: Close Up Publishing,

1994. 252.

Secondary

Sources

Read "Why Fiction Trumps Truth" By Yuval Noah Harari. Then choose

one essay from numbers 1-19 and one essay from the Biographical

selections, 1-3. Print, read, annotate and be prepared to answer the

following question: "How did reading these secondary sources help your

understanding of the novel?"

General

- The

Undying

Certainty of the Narrator in Tim O'Brien's The

Things They Carried. Steven Kaplan. Critique 35.1

(Fall 1993): p43-52. NOTE: if the link is not working on your

computer,

try lowering the privacy/security settings on your browser. If

that

does not work, click on the "Library Links" from the course

menu on the

left, go to "Literature Resource Center" and get this article

(hint:

search by subject "The Things They Carried" or author "Kaplan,

Steven.")

- Salvation,

Storytelling,

and Pilgrimage in Tim O'Brien's The Things

They Carried. Alex Vernon. Mosaic 36.4 (Dec.

2003): p171-188. NOTE: if the link is not working on your

computer, try

lowering the privacy/security settings on your browser. If

that does

not work, click on the "Library Links" from the course menu on

the

left, go to "Literature Resource Center" and get this article

(hint:

search by subject "The Things They Carried" or author "Vernon,

Alex.")

Coping

- Recovery

from Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms: A Qualitative Study of

Attributions

in Survivors of War.

- Developing a model of narrative analysis

to

investigate the role of social support in coping with

traumatic war

memories.

- Hope, Coping, and Social Support in

Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

- "Healing processes in trauma narratives: A

review." By: Kaminer, Debra. South African

Journal

of Psychology. Sep2006, Vol. 36 Issue 3, p481-499. 19p.

- From

the New York Times:

"The

Hollow

Man"

Truth

(note: if you decide to write about this for your essay, read 7, 9, 13 before writing thesis.

- "Relativism." Noel Castree, Rob Kitchin, and Alisdair Rogers. A Dictionary of Human Geography : Oxford University Press, 2013. Oxford Reference. 2013.

- Plato's Allegory

of

the Cave

- Relativism,

Truth,

Reality.

- "Saying

Good-bye to Historical Truth"

A 1991 essay by psychologist

Donald Spence.

- Reversing the Truth Effect: Learning the

Interpretation of Processing Fluency in Judgments of Truth.

Full Text Available

Academic Journal

By: Unkelbach, Christian. Journal of Experimental Psychology.

Learning,

Memory & Cognition. Jan2007, Vol. 33 Issue 1, p219-230.

12p. 7

Charts. DOI: 10.037/0278-7393.33. .219.

- Making Things Present: Tim O'Brien's

Autobiographical Metafiction. Silbergleid,

Robin. Contemporary Literature, Spring2009, Vol. 50 Issue 1,

p129-155,

27p. (Article) CLICK ON PDF TO READ THE ARTICLE. NOTE: if the

link is

not working on your computer, try lowering the

privacy/security

settings on your browser. If that does not work, click on the

"Library

Links" from the course menu on the left, go to "Literature

Reference

Center" and get this article (hint: search by subject "The

Things They

Carried" or author "Silbergleid, Robin.") PDF Full Text

(1.5MB)\

- `How to tell a true war story': Metafiction in

The

Things They Carried. Calloway, Catherine.

Critique, Summer95, Vol. 36 Issue 4, p249, 9p. (Literary

Criticism)

NOTE: if the link is not working on your computer, try

lowering the

privacy/security settings on your browser. If that does not

work, click

on the "Library Links" from the course menu on the left, go to

"Literature Reference Center" and get this article (hint:

search by

subject "The Things They Carried" or author "Calloway,

Catherine.") HTML Full Text

PDF Full Text

(283KB)

- David

Broyles "Why

Men

Love War

- "The

Most

Curious Thing" by Errol Morris -- on torture at Abu

Ghraib.

- From Ramparts magazine: "The

Whole Thing Was a Lie"

- How to Revise a True War Story John Young

- Kolbert, Elizabeth. "Why Facts Donít Change Our Minds." The New Yorker,

27 Feb. 2017. www.newyorker.com,

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/02/27/why-facts-dont-change-our-minds.

Accessed on 2, Nov. 2018.

Biographical

- Conversation

with

Tim O'Brien. Tim O'Brien and Tobey C. Herzog. Writing

Vietnam, Writing Life: Caputo, Heinemann, O'Brien, Butler.

Iowa City:

University of Iowa Press, 2008. p88-133. Rpt. in Short Story

Criticism.

Ed. Jelena O. Krstovic. Vol. 123. Detroit: Gale. Word Count:

21839.

From Literature Resource Center. NOTE: if the link is not

working on

your computer, try lowering the privacy/security settings on

your

browser. If that does not work, click on the "Library Links"

from the

course menu on the left, go to "Literature Resource Center"

and get

this article (hint: search by subject "The Things They

Carried" or

author "Herzog, Tobey." You'll have to click on the

"Biography" tab at

the top of the page.)

- A

Conversation with Tim O'Brien. Tim O'Brien and Patrick

Hicks.

Indiana Review 27.2 (Winter 2005): p85-95. NOTE: if the link

is not

working on your computer, try lowering the privacy/security

settings on

your browser. If that does not work, click on the "Library

Links" from

the course menu on the left, go to "Literature Resource

Center" and get

this article (hint: search by subject "The Things They

Carried" or

author "Hicks, Patrick." You'll have to click on the

"Biography" tab at

the top of the page.)

- An

interview. Tim O'Brien and Martin Naparsteck.

Contemporary

Literature 32.1 (Spring 1991): p1-11. NOTE: if the link is not

working

on your computer, try lowering the privacy/security settings

on your

browser. If that does not work, click on the "Library Links"

from the

course menu on the left, go to "Literature Resource Center"

and get

this article (hint: search by subject "The Things They

Carried" or

author "Naparsteck, Martin." You'll have to click on the

"Biography"

tab at the top of the page.)

On a different note . . .

General Essays on Vietnam

- The Long History of the Vietnam Novel New York Times

Radio

Essays

"Reel" Life Fiction as

Truth

PDF of novel

© 2001 David Bordelon

|

|